Becoming Beavers

An eclectic collection of 19 traditions that have shaped the OSU experience.

Part of the reason that the college experience stays with us is because there’s more to it than just going to classes and cramming for exams. From that first day gazing across the MU Quad, walking the paths of OSU-Cascades or logging in to OSU Ecampus, Oregon State students become part of a rich tradition reaching back to 1868. Not all traditions stick—and as we learned at press time, sometimes they’re unexpectedly interrupted—but they give us interesting insights into the community we love. Because even if you’re proudly stocked with orange gear and occasionally find yourself humming the OSU fight song, there’s always more to learn about what makes Beavers Beavers.

No. 1 — Rooks and Books

Beginning in 1919, students newly arrived on campus didn’t just absorb college tradition; they were quizzed on it. The administration sanctioned Vigilance Committee, made up of sophomores, published the yearly Rook Bible, a pocket-size handbook aimed at “instilling Beaver spirit.” First-year students, or “rooks,” were required to have the book on their person at all times and memorize its pages.

In addition to a brief school history and a collection of songs and yells that rooks were expected to be at the ready to recite, the handbook outlined rules for behavior. These included saluting the college president, attending all athletic events, refraining from dating (“fussing”) at games and not smoking on campus. (Students voted to lift the smoking ban in 1947.) Rook cadets wore green arm bands, other male rooks wore a green cap or “rook lid,” and female

rooks (“rookesses”) tied a green ribbon in their hair. At the end of May, during Junior Week end, students tossed these symbols of their rook-titude on a bonfire in a ceremony called the “Burning of the Green,” signifying

their advancement to sophomore status.

Over the decades, the handbook’s purpose broadened and the rules — particularly their enforcement by what would likely be considered hazing today — loosened. By the 1960s, rook green was required only on certain days. And after the Burning of the Green moved to Homecoming — little more than a month after students started school — that ritual, too, lost its significance.By the 1969-1970 handbook, mentions of these traditions were gone, thoughthey reappeared briefly and nostalgically in the mid-1990s. —SCHOLLE MCFARLAND

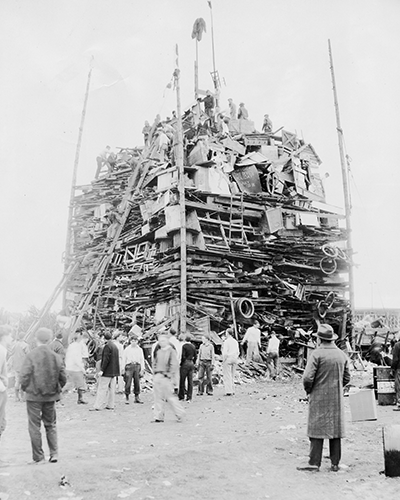

No. 2 — The Homecoming Bonfire

Originally known as the “Rook Bonfire,” this tradition — going back to the early 1900s — gave first year students the chance to earn bragging rights by building the tallest bonfire in school history. “A lot of students really responded to it,” archivist Karl McCreary said in a 2018 Daily Barometer interview.“You can see that in the old bonfires, which were 50 feet high. They would take anything they found in town, put it into this one huge, massive pile and just light it on fire. That was something that just can’t be done today on that scale.” The last-known bonfire was in 2013, when a few modest stacks of wooden pallets were torched on one of the last dirt parking lots on campus. As McCreary observed: “This university is growing so much, [there is no space] where you can have a place where you can burn something safely and not have asphalt melt, windows blow out or have a conflagration. If they have it again, they might have to move it out of town.” —KEVIN MILLER, ’78

No. 3 — Becoming Benny

How long has Benny been Benny? The Daily Barometer reported “pasteboard replicas of the Benny Beaver and Donald Duck families” decorating the walls for an inter-school dance way back in 1937. (Admission was 80 cents per couple.) But his transformation into the official school mascot — and a traditional part of game days — took a little longer. Here are some highlights: Today’s Benny, with his distinctive nose and buck teeth, has been around since 2005. Rumor has it that his head and costumes — along with the heads of all previous Bennys — are tucked away in a special room in Gill Coliseum.

No. 3 — 1941

One of the earliest mentions of a beaver named Benny — “who laughed in the red faces of experts” after the college broke Stanford football’s 1941 13-game winning streak — appeared in the 1942 yearbook. Made of wood, chicken wire and plaster of Paris, this Benny was wheeled into football games by the Rally Squad. It met its unfortunate demise in the fall of 1945 when it was “smashed to death by unknown assailants,” according to the Oregon Stater. The editor of the Daily Barometer, Bob Knoll, ’48, warned against seeking retribution: “Dynamiting of certain southern branch installations will not bring poor dead Benny back on this Earth.”

No. 3 — 1952

The first Benny to rally a game day crowd made his debut Sept. 18, 1952. The late Ken Austin, ’53, put together a costume of old shag carpet and was known for antics including climbing goal posts. As he explained to the Oregon Stater in 2004, “I was told to ‘liven things up.’ I immediately came back with ‘... well, what if I act like a rodeo clown?’”

No. 3 — 1964

Though the costume changed — with upgrades by members of the Home Ec Club — the grin remained the same from 1959 to 1969. Benny is seen here in a photo from the 1964 yearbook, posing with Rally Squad members Sandy Anderson (left) and Sue Wiesner Koffel, ’66.

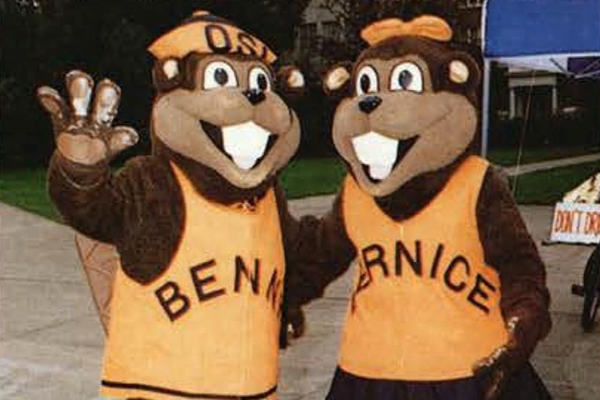

No. 3 — 1996

From 1984 to 1998, a fuzzier Benny was joined by a companion, Bernice. For Homecoming, Bernice donned a wedding dress and Benny sported a tux. Benny and Bernice were the second male and female mascot duo in NCAA history (after North Carolina State’s Mr. and Mrs. Wuf). —SCHOLLE MCFARLAND

No. 4 — Bruce the Moose

Alumni who attended OSU through 1995 likely recognize the lovable, taxidermied muzzle of Bruce the Moose. About eight feet tall from hoof to antler tip, Bruce once stood sentry at the entrance to the Horner Museum, where it was a tradition to rub his shoulder for luck.

Established 1925 (Bruce joined the collection in 1935), the museum gathered more than 60,000 artifacts and curiosities from around the world and was a draw for tourists and school children for decades. Its location, from 1950 to 1995, in the dank bowels of Gill Coliseum, had some drawbacks, as the Oregon Stater recounted: “Sticky syrup from soft drinks spilled by Beaver basketball fans dripped through the cracks of the coliseum floor and combined with dust loosened by thousands of stomping feet to endanger the collections and permanently damage several items.”

After budget cuts, the museum was closed, and Bruce vanished into obscurity. But at long last, now you can find him at the entrance to the new Corvallis Museum on Southwest Second Street. Check bentoncountymuseums.org/visit for details about how to pay a visit. —SCHOLLE MCFARLAND

No. 5 — The Orange and the...Black?

Oregon State University has had many names — Corvallis College, Oregon Agricultural College, Oregon State College — but one thing’s for sure, its colors have always been orange and black, right? Not quite. For 25 years, navy blue was the school color, until a faculty committee replaced it with orange in 1893. Students adopted black as the secondary color soon after, but its status was, surprisingly, a matter of some dispute. (Some speculate the reluctance to embrace black was due to Lewis & Clark College in Portland — known then as Albany College — having already adopted orange and black as their colors.) As a 1965 article in the Oregon Stater put it: “Over the years many have led themselves to believe that OSU’s colors are orange and black. It ain’t so.” Still, time — and decades’ worth of swag — eventually settled the question. Today’s official university brand guidelines embrace both Beaver Orange (Pantone 1665) and Paddletail Black.

No. 6 — Keepsakes of Courtship

Oregon State dances once came with an elaborate souvenir — the dance card. Tied with string around the wrist, these small booklets listed the evening’s songs with a space for the name of your dance partner next to each one. As they often captured first dances with future spouses, many survive in OSU’s archives, carefully preserved in scrapbooks. School dances started in 1897. Until the 1920s, there were just five a year, but soon student organizations got in the mix. “Fora Hawaiian-themed dance in the 1950s, big glass tanks were brought in and filled with hundreds of gold fish,”archivist Tiah Edmunson-Morton wrote. “In 1951, the MU transformed into the merry land of Oz … Instead of the Emerald City, students were invited into the Orange City — and were invited to view the world through orange-colored glasses, which doubled as a dance card.” By 1967, with social mores around courtship in flux, the roughly 70-year tradition came to an end. Still, expressions like “my dance card is full” or “pencil me in” remain, echoes of this once important part of student life. —SCHOLLE MCFARLAND

No. 7 — A Little Bit of the Islands

The bright sound of a strumming ukulele. The lingering scent of roasted kalua pig. For 68 years, Oregon State has celebrated the culture of Hawaii with the Hō‘ike, meaning “show” or“exhibit,” and Lū’au, meaning “feast” — OSU’s largest student-run event.

In the event’s first years, during the 1950s, only about 150 students hailed from Hawaii. (In 2022, there were 500.) Finding themselves 2,500 miles from home, they decided to bring a little bit of the islands to Corvallis and started an enduring tradition of sharing their culture with the OSU community and strengthening the school’s tight knit Hawaiian family.

This spring, 90 student dancers filled the LaSells Stewart Center to showcase dancing traditions, telling stories passed down through generations in chants and songs. Parents on the home islands sent about 380 pounds of native flowers, bushels of island greenery and other cargo like handmade jewelry, pineapple gummies and frozen kulolo desserts.

“Hula is about poetry and movement,” says Sandy Tsuneyoshi. Since the 1990s, the long-time OSU community leader affectionately known as “Aunty Sandy, ”has mentored the Hui O Hawai’i student club that puts on the festivities. Volunteers and students turned-chefs whip together menus in the Global Community Kitchen, blending local food and traditional fare: shoyu chicken, tofu poke and, of course, smoked kalua pork — 420 pounds worth this year. Tsuneyoshi has seen the event sell out venues for the past 27 years (except when the pandemic paused live events). This spring, Beavers snapped up all 1,200 tickets days before the festivities. —SIOBHAN MURRAY

No. 8 — The Ghost of Waldo Hall

Does an unearthly presence walk the floors of Waldo Hall? Does the former women’s dormitory house previous tenants who can never leave? Or is it simply a combination of urban legends and the quirks of a 116-year-old building

that give it that uncanny feeling? For decades, students and faculty have asked these questions.

Amas Aduviri, director of the College Assistance Migrant Program (CAMP), has had the same office on the third floor of Waldo Hall since 2005. During the early part of his career, he traveled frequently. He always carried pamphlets

with him, but one night around 2009, as he was packing for an early morning flight toWashington,D.C., he realized he’d forgotten to grab some.

When he got to the office, it was around midnight on a Saturday night. Campus was very quiet. Because Aduviri had heard plenty of stories about Waldo’s supernatural reputation, he was nervous going into the building so late.“My heart was racing,” he recalled. “I tried to go as fast as I could to get to my office.”

When he reached the third floor, he found lights off.As he reached for the switch, he saw a white figure with something draped over its body hovering by the staircase down the hall. It whooshed silently up the stairs toward the fourth floor. He said he felt the rush of air as it disappeared.

“I could feel the swish,” he said. “That freaked me out.”

Terrified, Aduviri rushed to his office, grabbed a stack of pamphlets and ran. He did not look back.

Waldo Hall opened in 1907 as a women’s dormitory. It is an imposing Richardson Romanesque-style building, the first on campus with indoor plumbing. Funny, since the second-floor women’s bath room is said to have some

of the most supernatural activity, with reports of creepy feelings, singing and full-bodied apparitions.

For 60 years ,Waldo housed generations of young women and was home to many notable female faculty members, including the university’s first librarian, Ida Kidder. (She becomes important to this story later.)

By the mid 1960s, severe neglect left the building at risk of being condemned, and for the safety of students, the dorms were emptied and the first three floors converted into office and classroom space. The fourth floor was sealed off.

There’s something about an abandoned space that lends itself to stories, and to ghosts. People began to report seeing figures in the upper-story windows. Footsteps, the clicking of high heels, and the sound of furniture being moved around were all reported by those working below. Had specters made themselves at home or were graduate students sneaking onto the dusty floor for some private time?

Several witnesses claimed to see a woman in 1920s-era attire wandering the building. Soon people began to wonder if this could be Ida Kidder, who had lived in Waldo during the turn of the 20th century.

Tiah Edmunson-Morton is an archivist at OSU Special Collections and Archives, and previously offered a ghost tour around campus that included Waldo Hall lore. She said long term building residents have passed down stories for years. “These definitely are good stories even if the facts behind them are a little shaky,” she said.

As to why Ida Kidder ended up being the figure most associated with the haunting, she speculates it was easy to cast her as a friendly ghost. “The mythology round her really solidified as maternal, caretaker, etc., and that made her an attractive, benevolent ghost,”she said. “Because while people like to be scared, they also like to be comforted.”

In 2010, after the infusion of stimulus money from the state, Waldo’s fourth floor was renovated and reopened as new office space.The conveniently creepy and dusty spot is now bright and lively once more. Aduviri, who saw the apparition before the remodel took place, says he hasn’t seen anything since. But, he adds, he also has made a point never again to visit the office late at night. —THERESA HOGUE

No. 9 — Well-Loved Watering Holes

A half-century has passed since Greg Little, ’73, earned his business degree at Oregon Sate, squeezing in school work around visits to Corvallis watering holes like the Oregon Museum, Mother’s Mattress Factory and Tavern, Lum Lee’s, Lamplighter, Goofy’s Tavern and the Beaver Hut. He notes that those last two were actually the same place — a bar sufficiently identity-challenged that it transitioned from Beaver Hut to Goofy’s and back, but with a strong North Star: a 10-tiny-beers-for-a-dollar special known as “Dimers.” (Dimers were so popular that you could also find them at Mother’s.)

Less than two years after graduating, Little put his extracurricular studies to entrepreneurial use when he helped launch his own tavern, Squirrel’s, located at the corner of Southwest Second Street and Monroe Avenue. (Little

got the nickname Squirrel as a sideline-chattering high school football player.) All these decades later, he is uniquely placed to talk about the tradition of Corvallis’ much-visited, well-loved bars.

“We became known as the ‘downtown learning center,’” he said of Squirrel’s. “A lot of graduate students, they became regular customers.You could find your prof there, ask him questions and get

information and not have to go to school per se.That’s always been kind of fun for us, having that rapport with that little bit older student.”

Once upon a time, Squirrel’s was part of a Corvallis bar scene that included Little’s college-era haunts plus other locales like the Night Deposit, the Class Reunion, the Peacock, Nendel’s, Don’s Den, Toa Yuen, the Stein Tavern, Murphy’s Tavern (in Southtown), Price’s Tavern and the Thunderbird Lounge.

The Peacock remains a downtown fixture, and Murphy’s relocated to downtown a few years ago, but all the other old stalwarts are gone — a testament to how hard it can be to run an enduring drinking establishment even in a college town. “Things have definitely changed. We still do quite a bit of beer, but others have gone to a lot of seltzers and ciders,” Little said.“I’ve got a few more years for sure. I just like the idea of a community gathering spot.” —STEVE LUNDEBERG, ’85

No. 10 — Everyone an Athlete

For over 100 years, Recreational Sports programs have helped students find community through the love of sport.

“Every man an athlete” was the mantra of A.D. Browne, director of the newly formed Intramural Athletics Program in

1916. He set the ambitious goal of at least 95% student participation in intramural activities. His goal was expanded in 1928 by Ruth Glassow, director of physical education for women, who declared, “A sport for every woman.”

Recreational Sports at Oregon State continues this legacy today as one of the oldest intramural programs in the nation. The Corvallis campus o"ers more than 50 intramural sport leagues, tournaments and events annually, and there are 39 student-run Sport Clubs (including seven equestrian-based ones). Basketball, volleyball and soccer continue to be popular, alongside new offerings. Adaptive sports include wheelchair basketball, sitting volleyball, goalball and beep ball. Esports allow students to compete on the virtual field, from NBA2K to Mario Kart.

Students can also navigate a canoe through the Dixon Recreation Center pool while playing water battleship, a competition where participants try to sink one another with buckets of water. —BRIAN HUSTOLES

No. 11 — Walking in His Footsteps

April 9, 1968. Five days after the assassination of Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., a nation mourned, and the Oregon State community took to the streets.

OSU President James Jensen dismissed university classes from 10 a.m. to noon and closed the library and campus offices. More than 1,200 students, faculty and townspeople gathered at the Memorial Union and solemnly marched downtown: a gathering so large, the Daily Barometer reported, that as the first of the procession reached the courthouse, students were still lined up back to the quad a mile away.

One day earlier, legislation to make King’s birthday a federal holiday had been introduced in Congress. Though it would take 15 years before the holiday was signed into law, in the interim, OSU students and faculty began their own traditions to honor the great civil rights leader.

The most enduring one began in 1983 when the university launched the Peace Breakfast, the centerpiece of OSU’s annual celebration of King’s life and legacy. Over the decades, the celebration has included guest lectures, films, community service, dances, awards and more.

Students also honored King from the 1980s into the 2010s with a candlelit walk from the Lonnie B. Harris Black Cultural Center (LBHBCC) to the Memorial Union. In 2017, this became the current Peace March held after the breakfast. Co-hosted by the cultural center and the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity, the one-mile march goes from the CH2M HILL Alumni Center, past the cultural center on Monroe and back to the Student Experience Center Plaza adjacent to the MU.

“The MLKPeace March commemorates Dr. King and also carries significance in reference to the OSU Black student walkout of 1969,” said Jamar Bean, LBHBCC director, referring to the significant nonviolent student action that happened after a football coach threatened to remove student-athlete Fred Milton from the team unless he shaved his goatee. Seeing this as discrimination, the Black Student Union organized, and 47 Black students symbolically

walked out of campus through the east gates. Talks afterward resulted in changes including the creation of the Educational Opportunities Program and the original Black Student Union Cultural Center.

“Dr.King’s legacy lives on in our students today, ”Bean said, “and continues to inspire them to be agents of change when faced with injustice and oppression.”—CATHLEEN HOCKMAN-WERT

No. 12 — Becoming a Bend Beav

Around 2018, student staff at OSU-Cascades in Bend created a new way to welcome students to their young, tight-knit campus. At the start of Welcome Week, first-year students painted rocks to reflect their aspirations. Then, the day before classes began, they were gathered for a “secret tradition.” Just after sunset, the students walked silently in single file along a candle-lit path to the top of a bluff over looking campus. Staff explained it was time to become Bend Beavs and instructed them to throw their painted rocks into “the pit” so that a part of them would forever be a part of campus. “It symbolizes each student’s connection to OSU-Cascades and their lifetime title of a ‘Bend Beav,’” Quentin Comus, ’23, explained. Students were often left speechless and teary. As enrollment grows and the Bend campus’s rough edges are developed, Student Affairs is readying to transform this tradition into something new. That’s why the secret, fondly held by many OSU-Cascades alumni, can now be revealed. —SCHOLLE MCFARLAND

No. 13 — "Oregon State, Fight, Fight, Fight!"

Oregon State's Fight Song is as instantly recognizable to Beaver fans today as it was more than a hundred years ago. A shortened version of “Hail to Old OAC,” written by alumnus Harold A. Wilkins in 1914, the Fight Song’s lyrics have changed slightly with the times to reflect the school’s changing name, as well as gender neutral language (“We’ll cheer throughout the land,” for example, replacing “We’ll cheer for every man”). Through it all, the spirit has remained the same. If you’re in Corvallis Friday night before a home game, you might catch the band playing it as they tour downtown bars after practice. (Find their route at beav.es/barband.) Watch a fun video of the 2018 Oregon State Choir surprising the MU Lounge with the full song at bit.ly/OSUfightsong. —SCHOLLE MCFARLAND

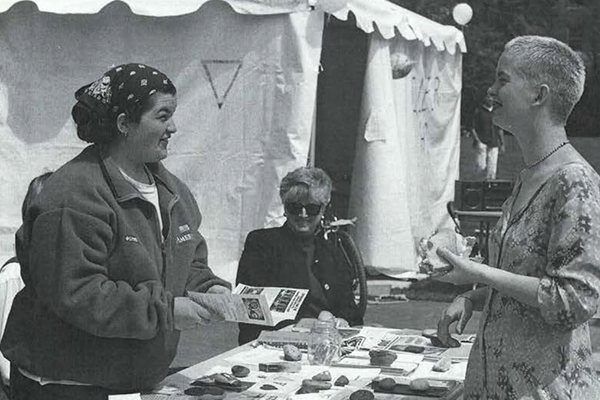

No. 14 — Pride Week

In the early hours ofApril 29, 1994, members of the Lesbian Gay Bisexual Alliance were camped out in a big tent on the MU Quad. It was only the third year Oregon State had celebrated what’s now known as Pride Week and the second with a tent. The first tent had been egged. Three people, later charged with criminal mischief, tried to pull up the stakes and knock it down. Holding space on the Quad, the students had concluded, required a 24 hour presence.

What sounded like a shot rang out around 2 a.m.

A figure was seen running away with what appeared to be a long-barreled gun. No one was ever caught or charged.

What happened next was a pivotal moment in OSU history. With university administration silent, student body President Brian Clem, ’94, and President elect April (Waddy) Berg,’99, stepped in. They organized a tent city to surround the Pride Tent. Members of student government and others camped out that night in solidarity; local merchants donated caffeinated supplies.

“We’re here basically just to show our support for LGBA,” Berg told the Daily Barometer. “When something like this happens to one community, it happens to everyone.”

About a month later, OSU President John Byrne established the Campus Commission on Hate Crimes and Hate Related Activity. The next year, Pride Week organizer Amy Millward noted a change in tone on campus: “We received so much support…people actually came to us to offer their help.”

University of Oregon students had established a Pride Week nearly 20 years earlier — they even advertised in the Barometer.“[In Eugene,] OSU is known as ‘Oregon Straight,’” Randy Shilts, managing editor of UO’s student newspaper, told the Barometer in 1975. (Shilts later authored the best-selling book And the Band Played On, chronicling the AIDS epidemic.)

But once OSU’s Pride Week tradition began, student organizers kept it coming back each May, despite controversy, conflict and — at least for the first decade — a steady stream of angry letters. Over the past 30 years, the week has featured speakers, dances, panel discussions and more in the name of, as the 1996 year book put it, “friendship and visibility.”

Camping out in the tent remained a part of the tradition for years, though later it became more festive and involved marshmallows. After the Pride Center building opened in the fall of 2004, students instead held a “slumber party” there. —SCHOLLE MCFARLAND

No. 15 — Graduation Teas

Nearly all that remains of a tradition that started and stopped from the 1930s through the 1990s are about 100 teacups and saucers carefully wrapped and stored in the Hawthorn Suite in Milam Hall. In the 1930s, women graduates across campus began gathering upstairs in the Women’s Building for tea as part of a Commencement celebration. Nationwide, it was rare for a woman to attend college at this time. In 1930-31, only a quarter of college students were women. To honor the occasion, each participant donated a teacup and saucer, signing their name and graduation year on the bottom. At some point, the tea parties stopped, but women in physical education picked it back up, and the custom continued through the mid-1980s, led by staff in the then College of Health and Physical Education (now called the College of Health, see p.20). In the mid-1990s, faculty briefly revived the tradition, using the cups at a Commencement brunch. This time, the event included men. Former staff member Michelle Mahana recalls a male graduate shyly producing a cup and saucer, saying his grandmother had requested he take part in the tradition as she had. After a few years, the tea parties died out once more, leaving behind cups, saucers and memories. —KATHRYN STROPPEL

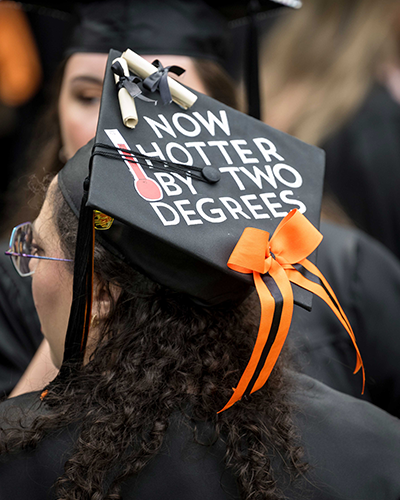

No. 16 — Custom Caps

Commencement is perhaps the most traditional of university events, tying the experience of today’s graduates to those across the decades. Within the great event are myriad noteworthy OSU traditions. Once frowned upon, decorating graduation caps (which appears to have started in the 1990s) is now so common that the OSU Alumni Association has held cap decoration events, and a May piece in The New York Times Style Section featured companies making tidy profits creating trendsetting cap designs. Meanwhile, many graduates of OSU’s Civil and Construction Engineering program wear black hardhats instead.

No. 17 — Diploma in Hand

Even as the number of graduates at the Corvallis ceremony has soared above 7,000, OSU has clung to the idea that grads should get their real diplomas at Commencement, rather than (as they’d get at most other large universities and many small ones) a note saying “Congrats, yours is in the mail.” This tricky business used to be accomplished by forcing students to march and sit in alphabetical order within their college groups, but now it’s based on a constantly self-correcting system involving cards that get handed in as graduates approach the podiums, and a small army of employees and volunteers who scramble to keep diplomas in the right order.

No. 18 — Removing the Gown, Taking the Oath

A particularly moving Commencement tradition happens when a senior military officer goes to the podium. Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) grads — 30 this past June — remove their cap and gown, stand in military head wear and uniform, and accept their commissions as officers.

No. 19 — One University, Many Special Moments

Graduates of OSU-Cascades follow the bagpipes in a ceremony in Bend, while across the Corvallis campus before and after the main Commencement ceremony, groups of graduates gather for special moments together.

OSU Ecampus typically has brought together its graduates-to-be in the Valley Library Rotunda — or, more recently, at the MU — on Commencement morning. Some students are meeting their professors and seeing the campus in person for the first time.

Outside one of these gatherings a few years ago, a young mother in cap and gown took photo after photo of the surroundings, including an old-style lamppost outside Kerr Hall, as her parents stood nearby, each holding one of her children. Asked what she was doing, the soon-to-be Ecampus grad said, “This is my university, and I’ve never seen it before!” — KEVIN MILLER, ’78