Bronze statue honors the legendary high jumper, who died March 12

Beaver Nation mourns the loss of one of the university's most celebrated alumni, Dick Fosbury, '72, who died on March 12, 2023. OSU honored his contributions to his sport, and to the university, when a bronze statue was unveiled at the Corvallis campus in 2018, immortalizing Fosbury's athletic achievement. “This is something I’ll never forget,” he said; his OSU family, and the world, will never forget him. Here's the story of the statue and OSU's golden rebel.

From the Fall 2018 issue of the Oregon Stater magazine

By Kevin Miller

It’s a good year to be Dick Fosbury.

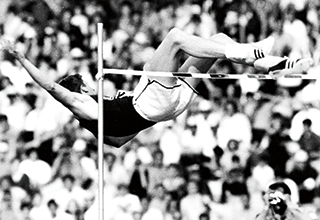

On Oct. 19, a day short of 50 years after his gold medal high jump at the Mexico City Olympics made him a worldwide celebrity, he will stand at the site of old Bell Field in front of Dixon Recreation Center and help unveil a majestic bronze sculpture of himself soaring over a bar exactly 7 feet, 4 1/4 inches above the ground.

For generations, students and others will look up and there he’ll be, frozen in that singular moment in 1968.

Since his teenage years in Medford, he had fought off skeptics to perfect a backward technique — the Fosbury Flop — that many deemed ridiculous and dangerous. He earned a scholarship to OSU and won two collegiate championships for the Beavers, but he barely made the U.S. team during a quirky Olympic trials. As the Olympic high jump competition approached, he faced 14 other men who had also cleared 7 feet. Soon, almost all Olympic high jump medalists would be floppers, but on that day he was the only one doing it backward. In front of 80,000 astounded fans, he dragged himself up, over and into history, his arms spread in triumph.

The 1972 engineering graduate said the sculpture, crafted by Ellen Tykeson in her Eugene studio, is among the best things that have happened to him.

“I’m really excited about it,” Fosbury said. “It’s so awesome. She’s amazingly talented. I’ve had a lot of awards; it can get silly. And once, I was the best in the world at what I did."

“The statue is a great honor. It doesn’t happen to many people at Oregon State. Fortunately, I’m alive to get to see it!” - Dick Fosbury, '72

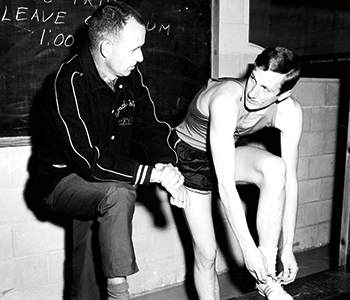

Fosbury said he admires sculptor Ellen Tykeson’s desire to get the details right. He loaned her a pair of his old jumping spikes to help with that. (Photos by Hannah O’Leary)

Fosbury never said a peep about it, but a lot of people have been puzzled about the lack of permanent recognition for him at OSU. Maybe it was because the university ended its men’s track program in 1988. Maybe it was because of old memories of him supporting counter-culture causes during a tumultuous time on campus. Whatever the reasons, he was something of an orphan in Beaver Nation.

Elsewhere, car companies and other corporations around the globe used his name and image to tout innovation and out-of-the-box thinking. A European design firm sought to be a disruptor of the status quo, so it named itself “Fosbury,” as did little cafés and other businesses around the world.

As the 50th anniversary of his Olympic win drew closer, his old roommate and fraternity buddy, Bryon Van Fleet ’68 ’72, teamed with other Theta Chi brothers to lobby and pester OSU officials to seize the opportunity to re-embrace “The Foz.”

Above, longtime OSU men’s track coach Bernie Wagner checks in with his star jumper. (Photos courtesy OSU Special Collections and Archives Research Center)

“Bryon really carried my water on this one,” Fosbury said with a chuckle. OSU president Ed Ray got involved, eventually decreeing that the university would find a way to give Fosbury his due. Hence the unveiling ceremony, planned for the afternoon of Oct. 19, and other activities.

A cancer survivor, Fosbury lives in Bellevue, Idaho, population about 2,300, where he has been a consulting engineer, is a member of the planning and zoning commission, and is expected to win a seat on the Blaine County Board of Commissioners in the November election.

The long-form story of how he invented the Fosbury Flop, and what happened before and after Mexico City, and how his little brother’s death and the subsequent explosion of his once-tight family helped give him the toughness to try his weird technique in front of snickering classmates in high school, is presented in detail in a new biography, "The Wizard of Foz: Dick Fosbury’s One-Man High-Jump Revolution," written with Fosbury’s help by Eugene author Bob Welch and recently published by Skyhorse Press.

“This is my life, and how I grew up,” Fosbury said of the book. “It’s what happened.

Fosbury greets a fan — in this case Dean Javier Nieto of the College of Public Health and Human Sciences — after receiving the OSU Alumni Association’s highest honor, the E.B. Lemon Distinguished Alumni Award in spring 2017. (Photo by Hannah O’Leary)

He expects to be accompanied at the unveiling by family, OSU friends and possibly some other members of the 1968 U.S. Olympic team, with whom he has remained close, he said, “like a family.” He keeps in touch with sprinter Tommie Smith, who — at his own gold medal ceremony in Mexico City — joined teammate and bronze medalist John Carlos in raising a black-gloved fist in protest against racial inequality in the U.S. and elsewhere. Fosbury did not take part in that protest, but was moved by it. He became more active in social causes when he got home.

Like so many of the university’s most accomplished and innovative alumni, Fosbury was no star in the classroom. He flunked out of engineering and was thrilled when Dean George Gleeson — after the gold medal hoopla let up — offered him a second chance if he agreed to quit jumping and focus on his studies.

“I was grateful for that,” he said. “I went to Oregon State because I wanted to be an engineer.” Even with fewer distractions, classes remained a challenge, but he earned his B.S. in March 1972 and had the university mail him his diploma.

Wrote Welch: “He didn’t attend the ceremony, feeling embarrassed about how long it had taken, but treasuring it almost as if it were Olympic gold.”

More on Dick Fosbury: