From the Spring 2023 issue of the Oregon Stater magazine

1. Corvallis is the birthplace of the modern maraschino

The bright red cherry on top of your favorite treat has an OSU story to tell. Soon after Ernest H. Wiegand, a professor of food sciences and technology, arrived at the university in 1919, he was approached by cherry growers eager to figure out what to do with the delicious, but delicate, Queen Anne cherries that flourish in Oregon but spoil quickly and become mushy when preserved. In response, Wiegand (the namesake of, you guessed it, Wiegand Hall) developed the modern brining method — which adds calcium salts to the brine to firm up the fruit — that remains standard to this day.

2. Alumni helped launch Oregon’s craft beer revolution

Next time you enjoy an IPA at an Oregon brewpub, raise a glass to the Beavers who helped make it happen. In the mid-1980s, a group of brewers that included three alumni with familiar names — Rob Widmer, ’96; Mike McMenamin, ’73; and Brian McMenamin, ’80 — teamed up to overturn a Prohibition-era Oregon law that had made it illegal to brew and sell beer on the same premises for nearly 70 years. Their efforts resulted in the 1985 “Brewpub Bill.” It was defeated by lobbying from wholesale beer suppliers, but its language was tucked into another bill that passed into law on July 13, 1985. The McMenamin brothers opened the state’s first modern brewpub — the Hillsdale Brewery & Public House in Southwest Portland — that year. The industry now creates more than 40,000 jobs in Oregon with a total economic output of $6.6 billion, according to the biennial Beer Serves America report.

3. There’s a little-known O.J.-ice cream-OSU connection

Conscious in 1994 and 1995? Then you likely remember the national media frenzy that accompanied the 11-month trial of former NFL star O.J. Simpson for the murder of his wife Nicole Brown Simpson and house guest Ronald L. Goldman. But what you might not know is that an OSU alumnus and professor was called in to play a small part in Simpson’s eventual acquittal. When building the case that police ignored and mishandled evidence that could have better established the victims’ time of death, many pointed to a melting cup of Ben & Jerry’s ice cream found on a staircase at Nicole Brown Simpson’s condo shortly after her body was discovered. Professor emeritus Floyd W. Bodyfelt, ’63, M.S. ’67, an ice cream expert, ran tests for the defense to replicate the meltdown rates of the three flavors — Chocolate Chip Cookie Dough, Rainforest Crunch and Chocolate Fudge Brownie — found at the condo. Alas, he never took the stand.

4. Oregon State researchers saved the hazelnut

When the fungal disease Eastern filbert blight — first discovered in the Willamette Valley in 1986 — nearly collapsed the hazelnut industry, it was OSU researchers who developed resistant trees. With these, acreage expanded from 29,000 in 2009 to 93,000 today. The most popular OSU-bred cultivar, Jefferson, released in 2009, now accounts for more than half the total acres planted. In all, 99% of U.S. hazelnuts are grown in the Willamette Valley with a total economic impact in Oregon of about $167 million, according to the USDA. “Without the resistant cultivars from OSU, the industry would have been wiped out,” said Professor Shawn Mehlenbacher, the expert behind the program. His work built on that of Maxine Thompson, professor emerita, who began OSU’s hazelnut breeding program in 1969, as well as Ron Cameron, professor emeritus, who did early research into Eastern filbert blight. Oregon State is known internationally for its hazelnut breakthroughs, and the combined genetic collections of the USDA-Agricultural Research Service and Oregon State are, according to Mehlenbacher, “by far the best hazelnut collections in the world.”

5. An alumna helped build the Betty Crocker brand

If you’ve ever purchased a cake mix in a box emblazoned with a red spoon, you’ve encountered the Betty Crocker brand. It was a pioneering alumna, Mercedes Bates, ’36, who helped make it an enduring household name. The Betty Crocker character was created in 1921 and popularized by a radio show and a series of best-selling cookbooks. But during Bates’ time as director of the Betty Crocker Food and Nutrition Center and as the first woman to serve as a corporate officer of General Mills (1964 to 1983), tremendous cultural shifts were underway, as women began to work outside the home in record numbers. In 1972, the National Organization for Women even filed a bias complaint against General Mills, charging that the Betty Crocker brand stereotyped women. With Bates’ leadership, Betty Crocker adapted to the times and hung onto her status as a cultural icon. Bates’ OSU degree in food and nutrition — from the first West Coast university to offer home economics — was the foundation for it all. Made possible by a gift from Mercedes Bates, the OSU Child Development Center, in Bates Hall, opened in 1992 as the nation’s first center dedicated to studying families throughout their lifespan.

6. OSU is home to some of the world’s longest-running agricultural experiments

There’s no doubt farming affects the land, but it’s hard to tell how if you don’t take the long view. OSU’s Columbia Basin Agricultural Research Center, known as CBARC, in Pendleton, is home to the West’s longestrunning agricultural experiments (which also rank among the top 10 longest running in the world). Test plots of wheat, barley and peas show the long-term environmental costs and benefits of different farming practices like using manure versus using fertilizer or tilling with an old-fashioned moldboard plow versus not tilling at all. “Some of these plots were started in the 1930s and show us what happens when we farm how people did 90 years ago,” said lead scientist Stephen Machado. “We’re fortunate to have inherited a treasure here. We’re still learning lessons and finding out new things every year.”

7. OSU gave the “king of blackberries” its crown

Marionberry jam, pie, ice cream, cocktails — in Oregon you can find these big, juicy berries in everything. Developed by a renowned USDA horticulturist as part of Oregon State’s blackberry breeding program, marionberries are so popular that they almost attained “state berry” status in 2009. (At long last, marionberry pie, at least, succeeded in becoming the state pie in 2017.) A cross between Chehalem and Olallie blackberries, the marionberry was developed by George Waldo, ’22, and released for public consumption in 1956. (Waldo is also responsible for the popular Hood strawberry.) They take their name from Marion County, where most of the breeding trials took place. More than half the blackberries Oregon grows are marionberries — upwards of 33 million pounds a year — but the state gobbles up the bulk of them before the rest of the U.S. ever gets a bite.

8. An OSU art contest has celebrated food and farming for 40 years

Apples yellow on the branch, a wooden pushcart loaded with orange pumpkins — food isn’t just good to eat, it can also be beautiful. Since 1983, the College of Agricultural Sciences has sponsored a one-ofa-kind “Art About Agriculture” competition, now in its 40th year. Both professional and emerging Pacific Northwest artists submit works each spring. In order to reach urban and rural audiences, the exhibition tours the Pacific Northwest annually. A subset of the exhibited artwork is purchased and added to the university’s permanent collection, which at 410 pieces is the university’s most active art collection and includes works from celebrated Oregon artists such as Sally Haley and Rick Bartow. (“Crab Season” by Robin Hostick, ’91, is shown here.) Check out the tour schedule at beav.es/ag-art.

9. Many products you love started in OSU’s Food Innovation Center

If you’ve eaten a Ruby Jewel ice cream sandwich, enjoyed a scoop at Salt & Straw or cozied up to a Bob’s Red Mill oatmeal cup, you’ve had a close encounter with a product born from Oregon State’s Food Innovation Center. One of the university’s many research stations and a multidisciplinary partnership with the Oregon Department of Agriculture, the Food Innovation Center was established in Portland’s Pearl District in 1999. Here, budding food entrepreneurs and large food companies work out their newest masterpieces in the incubator kitchen, consult with food scientists to formulate new flavors, learn how to scale production efficiently and safely, test shelf life and draw on the center’s enormous database of taste testers to discover what’s working and why. (See “The Big Picture,” page 2.) The manager of the FIC’s product and process development team, Sarah Masoni, ’87, is so well known in food circles that Chris Spencer of small-batch ice cream makers UpStar described her to The New York Times as “the million-dollar palate.”

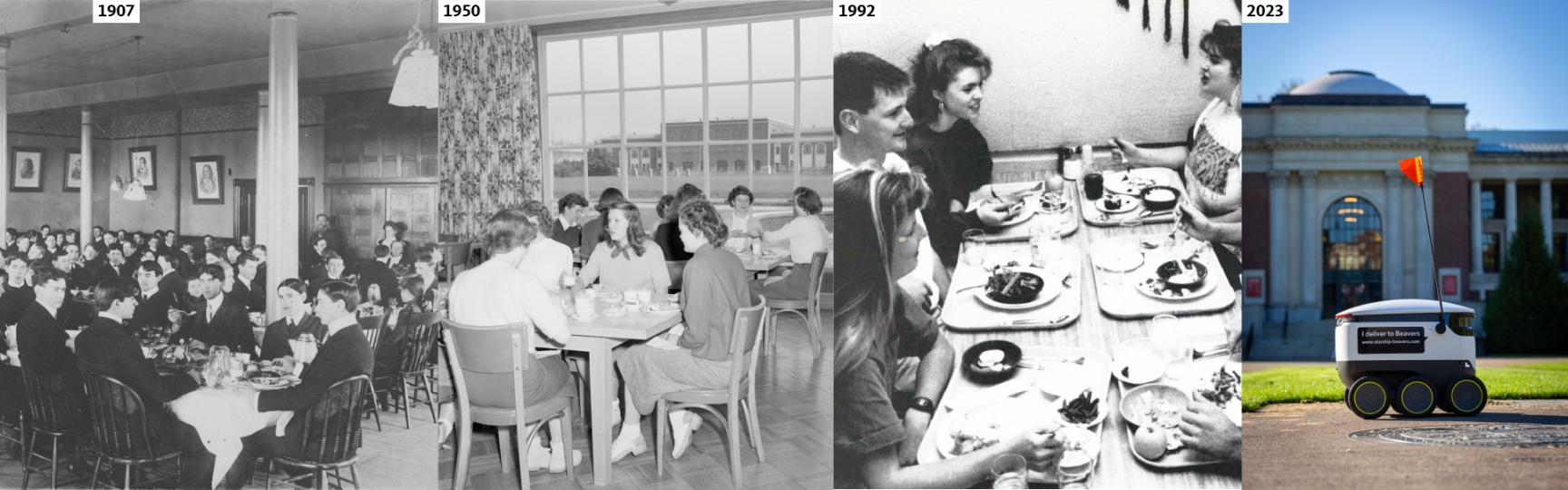

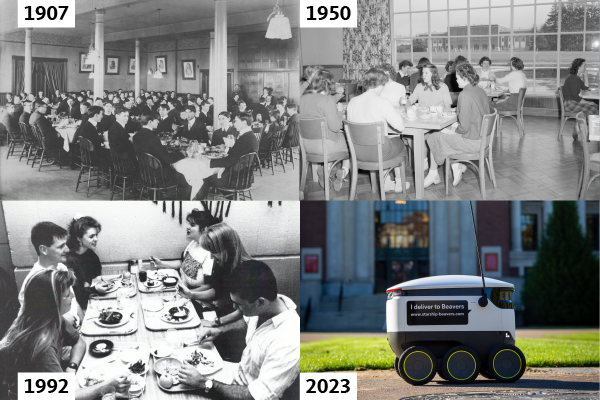

10. Campus dining has changed a lot

From link sausage and buttered cabbage in the 1940s, to fishwich and potato chips in the 1970s, to today’s build-your-own grain bowls and green goddess smoothies, the dining experience at OSU has changed considerably over the years. But it’s not just what’s on the plate that’s different. Take, for instance, pants. They were considered improper for women, not just at the dinner table but anywhere on campus, until 1970 when women’s clothing guidelines dropped from the student handbook. And who would have ever guessed packs of robots would one day roam campus delivering meals?