Illustrations by Kathleen Fu

The social distancing dots outside grocery stores are peeling. Shortages of toilet paper, baby formula and yeast are no more. The daily recounting of casualties is done. But even as the worst of the pandemic recedes into the rearview mirror, the fact is that four years ago the world changed. Oregon State’s public service-minded researchers and outreach specialists remain focused on learning from all we went through. From lasting changes to the way classes are taught to inventive ways to protect our health as a community, here’s a look at some of the lessons.

Lesson #1: Flexibility makes college classes better

When the nation hunkered down in March 2020, nearly 2,000 OSU faculty members had two weeks to reboot spring term courses in fully remote mode. The Center for Teaching and Learning and its partners consulted with hundreds of faculty, while Ecampus and its nationally renowned team of instructional designers scaled up training and extended their expertise to the entire faculty.

Most faculty members knew of and had even used the Canvas online learning management system, but suddenly it and Zoom were the hub of nearly all instruction at OSU. When students resisted the less personal approach, many instructors shipped out boxes of materials for hands-on lab activities, while others designed small Zoom breakout room activities where everyone worked to keep the fun in learning.

At first it seemed to work, said Regan A. R. Gurung, associate vice provost and executive director of the Center for Teaching and Learning: “I teach a 400-person class and often can barely see facial features of those in the back. Teaching remotely made every student the same size on my screen and in some ways provided more equal access to me.” But as the pandemic wore on, more students wearied of the format and turned off their cameras.

Gurung collaborated with more than 40 educators at universities across the country on the book Higher Education Beyond COVID, released in fall 2023. A key takeaway: Faculty and students did better when remote classes were organized but flexible, providing multiple ways for students to learn and engage.

Gurung sees evidence of lasting benefits to the upheaval caused by COVID. Almost all general-purpose classrooms across the Corvallis campus are now wired and equipped for web collaboration. The Center for Teaching and Learning is training faculty in new methods that ensure that the system will be more prepared for all sorts of future disruptions, from extreme weather to wildfires.

Many now record classes so students who are sick — or who might benefit from listening to the material again — don’t miss out. Some also still provide live Zoom access so students can participate if they can’t make it in person.

“The pandemic had higher education scrutinize much of what we took for granted, or at the very least, the pedagogical practices that had not changed in a long time,” said Gurung. — Siobhan Murray

Lesson #2: In a crisis, a lab is a lab

It’s hard to make public health decisions when basic information is scarce. The nation faced the onset of the pandemic with COVID-19 testing supplies and facilities in short supply. But the scientists at the Oregon Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, housed within OSU’s Carlson College of Veterinary Medicine, knew they had the expertise and equipment to serve the people of Oregon as well as their pets.

Many pathogens that affect animals also affect humans — rabies, swine fl u and COVID-19 are well-known examples. The OVDL, like other veterinary labs across the country, recognizes the connections between the health of people, animals and the environment. The lab also has the capacity to test at scale, as many pathogens spread rapidly among livestock operations housing thousands of animals.

Early on, when the lab’s leadership reached out to public health officials and offered to help with human COVID-19 testing, “They pretty much poo-pooed the idea be-cause we were ‘just a vet lab’,” said Donna Mulrooney, quality assurance manager for the OVDL.

The lab pushed its case while also applying for, and receiving, a federal certification that allowed it to handle human samples. Oregon’s public health officials were won over, and the OVDL process ed more than 300,000 PCR tests from across the

state. Included were all PCR tests for Oregon State University’s TRACE COVID-19 public health surveil-lance project. —Jens Odegaard

Lesson #3: Sometimes online learning is accessible learning

Biscuitroots, buttercups, red bells and silver lupine — Rachel Werling, coordinator of the Extension Land Steward Program, often guided groups along the trails of southern Oregon’s Rogue Valley to enjoy these and other wildflowers in the spring. With group hikes shut down by COVID, she posted two wildflower walks online.

The videos have been viewed almost 1,000 times. “Thank you. Thank you,” one viewer wrote. “I am disabled and cannot (yet) hike to see these and I am thrilled to see new and old flower friends. This means so much that when I saw the lupines, I cried!”

Until 2020, the Oregon State University Extension Service relied on in-person outreach for classes, workshops and events. Then COVID-19 led to a boom in virtual attendees from all over the United States and abroad.

When the Oregon City-based Tree School Clackamas — a one day event about managing and caring for private woodlands — was shut down by the pandemic, the 2020 Tree School Online was born of necessity. The webinars drew more than twice the

attendees of the in-person events in 2019. That growth continued into 2021, and the recorded webinars have been watched nearly 17,000 times on YouTube.

Though some parts of in-person classes can’t be beat — it’s not so easy to get hands-on experience using a chainsaw through Zoom — the pandemic dramatically broadened the use of online trainings.

“We learned that the format of Tree School Online worked very well, bringing in a diverse group of speakers, offering live webinars and recording the sessions to make them accessible for future use,” said Glenn Ahrens, M.S. ’90,

OSU Extension forester in Clackamas, Hood River and Marion counties.

As it turns out, remote babysitting workshops work well, too. The first year COVID pushed the training online in the Columbia River Gorge, 38 teens earned their Oregon 4-H Babysitter Certificate. In 2022 and 2023, a statewide virtual babysitting workshop certified a total of 368 youths from across the state. —Chris Branam

Lesson #4: Burnout requires more than one solution

As the COVID-19 virus swept the nation, boundaries between work and personal life blurred while people worked from makeshift home offices, faced their own or family members’ illness, cared for children and loved ones, and dealt with unpredictable and constantly changing circumstances. Burnout threatened success in all areas.

In the spring of 2020, OSU faculty members Kathy Becker-Blease, Katie Gallagher and Regan A. R. Gurung launched the “Punch Through Pandemics” online course to explore the science of stress and find evidence-based skills for coping. It enrolled 200 OSU students and was offered free to the public, with nearly 4,000 people across the world participating. (See the professors’ tips in the sidebar “Beating Burnout.”)

Among the suggestions: spend time in nature, cultivate plants at home, practice meditation, take walks and engage in other exercise (like cold-water swimming). Gurung remembers a student who shared views from a hike he was on with his class via Zoom. Other students shared art they had created.

Two years into the pandemic, Gurung followed up with the Brightside Project, inviting students and faculty to share essays, memes, poetry, music and more about how they managed the ups and downs of the COVID-19 era. The pieces from that project are archived at OSU’s Valley Library.

People primarily cite rest and relaxation as cures for burnout, but after delving into faculty stories for the book Higher Education Beyond COVID, Inara Scott, senior associate dean in the College of Business and Gomo Family Professor, realized avoiding burnout is not a one-size-fits-all proposition.

“The recommendations I kept hearing — most of which seemed to involve stepping away from work and ‘self-care’ — didn’t seem to hit the mark for me or many people I knew,” said Scott. “My burnout comes when I feel like I’m not making a difference. For my form of burnout, it’s important for me to lean into those experiences that make meaning and help me see the impact of my work on students and faculty.” —Siobhan Murray

BEATING BURNOUT

- Remember your “why.” Align your time and energy with what is meaningful to you.

- Block out time away from news, technology and social media.

- Practice mindfulness activities, like walking meditations in nature, doodling and listening to calming music. It’s all about taking deep breaths in … and out! (See suggestions at beav.es/mindful.)

- Make regular time for the important people in your life and show them they’re important.

- Let your self-care activities nourish you versus being just more “shoulds” on your to-do list. What activity feels like a welcome gift?

- Find small, sincere ways to take stock of, and celebrate, your accomplishments.

- Treat and talk to yourself like you would a good friend — with understanding, generosity and compassion.

(Find ways to practice at self-compassion.org.)

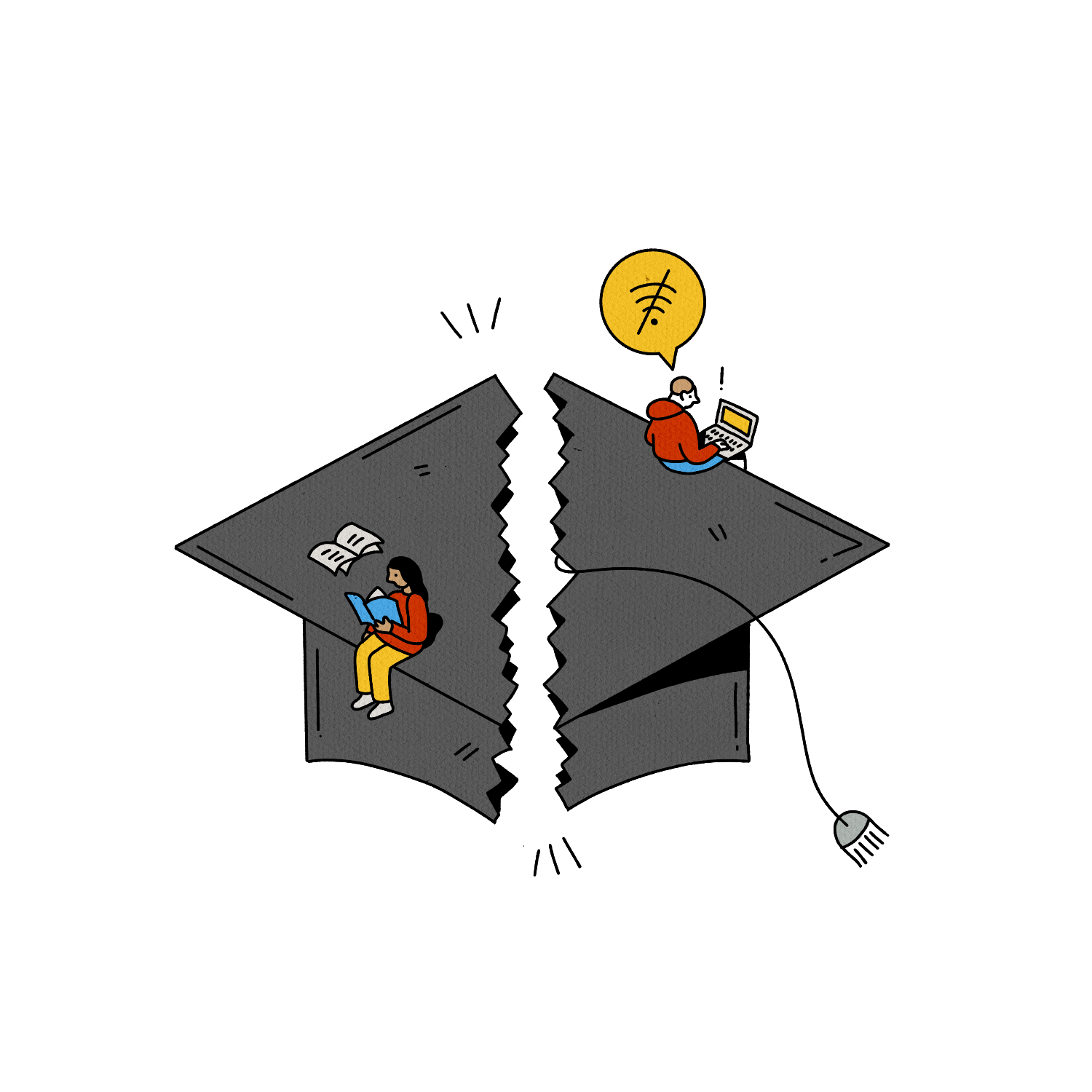

Lesson #5: Learning interrupted by COVID won’t get better on its own

The COVID-19 pandemic caused the biggest disruption in the history of American education. Most of Oregon’s 553,000 public school students went without in-person classes for more than a year. Now a $6.9 million federal contract is helping the OSU College of Education build a program known as Equitable Accelerated Learning in K-8 Literacies and Mathematics (or ALK-8). It brings together kindergarten through 8th-grade instructional leaders, OSU education faculty and Oregon Department of Education experts to learn how to support students and teachers as they work to identify and regain what was lost.

“We continue to have larger numbers of students that are not yet reading at grade level compared to pre-pandemic outcomes,” said Chrissy Chapman, director of teaching and learning for the Woodburn School District. She’s part of an ALK-8

working group seeking effective ways to help bilingual students access grade-level content and fill learning gaps. Many children lacked access to necessary technology or internet bandwidth. Online learning also proved extra challenging for students

with disabilities and language barriers.

“The members of the working groups have some of the greatest insight into potential improvements because they are directly connected to designing, refining and implementing solutions to the challenges students and teachers are facing,” said Jana Bouma-Gearhart, associate dean of research for the College of Education.

Lesson #6: Veterinary researchers can help protect us against future outbreaks

The next time a highly contagious disease jumps from animals to humans, Carlson College of Veterinary Medicine researchers will not be caught unawares, partly thanks to a two-year, $1 million cooperative agreement with the U.S Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service to continue work to understand, detect and combat zoonotic diseases.

Brian Dolan, an associate professor of immunology at the college, leads a team testing wild animal specimens for the virus responsible for COVID-19. They want to learn which animal species can harbor and transmit the virus. They’ll also sequence the viral genome of SARS-CoV-2 whenever they find it to determine whether the strain is related to recent COVID variants spreading among humans or if it has evolved independently through animals.

“There’s always the potential for the virus to establish itself within an animal species permanently, and if that happens, there’s potential for it to be passed around among wild animals and then later spill over into humans,” said Dolan, noting that this unlikely scenario could have disastrous implications.

The research focuses on mammalian species that may encounter humans, such as rodents and bats. The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and various wildlife rehabilitators help provide samples.

“From my standpoint, this project re-emphasizes the ‘one health’ mission of the lab,” said Kurt Williams, director of the college’s diagnostic facility. “We don’t deal only with diseases that affect nonhuman animals; we do lots of work that directly relates to public health.” —Molly Rosbach

Lesson #7: Cities are like organisms — they need immune systems

Viruses can reproduce rapidly, taking over cells and turning them into viral factories within hours. Individuals’ immune systems need to rise to the challenge, but what happens when they can’t, and a whole population gets sick?

As the early days of the pandemic demonstrated, cities can struggle to stop the momentum of a spreading disease. Armed with community input and lessons learned over the past four years, a multidisciplinary team of researchers at Oregon State University is designing city-scale feedback loops to act as a kind of immune system for a population as a whole.The team is supported by $1 million from the National Science Foundation, through its Predictive Intelligence for Pandemic Prevention Program (PIPP).

The project began in 2022 with a series of workshops in cities across Oregon. “One key that communities stressed was the importance of sharing timely data between different groups and organizations — much like how different systems in the body communicate to mount an immune response,” said team member Katherine McLaughlin, an applied statistician.

The researchers aim to establish a center at OSU that combines mathematical and computational modeling with engineering, public health and public engagement. The Center for Pandemic-Resilient Cities (CPARC; pronounced like “spark”) will prototype city-scale feedback loops that link environmental monitoring with epidemic forecasting and communication, so responders won’t have to play catchup after an outbreak begins.

Led by the College of Science, the effort capitalizes on OSU’s strong tradition of multidisciplinary work and includes six university colleges. In the College of Engineering, Tyler Radniecki and Christine Kelly are developing innovations in wastewater sensing, a low-cost method of monitoring that involves testing sewage samples for disease.

Teams from the College of Health and OSU Extension and Engagement are working to ensure that the science incorporates the characteristics of different communities. For example, responders in cities with a lot of tourism need to know whether infection

is spreading locally, such as within schools, or is arriving from other cities, as responses will be different in each case.

Faculty from the College of Liberal Arts (Daniel Faltesek) are researching how to use interactive media to communicate infectious disease forecasts to people in the city, to close the loop between prediction and prevention.

“Human systems, like cities, can be very good at making things ‘go viral,’” said project leader Dalziel. “Using mathematics, engineering and community engagement, we can develop systems that make helpful responses go viral, too.”

—Hannah Ashton