From the Spring 2023 issue of the Oregon Stater magazine

By Suzanne Pardington Effros

Beth Klingner watched the sky turn orange over the ridge from her family’s 60-acre Dion Vineyard, tucked in the Chehalem Mountains.

It was September 2020, and she was out picking the first grapes of what had started as a beautiful year for Oregon wine. Early rains had kept the crops small, but after a dry, warm summer, they were ripe and ready to go. Then came strong winds and a record-setting wildfire season across the West.

As smoke billowed into the air from a nearby wildfire, Klingner knew the entire 2020 Oregon wine industry could go up with it. Not because the grapes would be consumed by fire, but because the acrid taste and smell of smoke might taint the wine.

“It was horrifying,” she said. “It got quieter and quieter because it was so weird and eerie. We all stopped for a while and then kept picking. We had to get the grapes off the vine faster.”

In Corvallis, Associate Professor Elizabeth Tomasino’s phone started ringing off the hook. She is a wine chemist and sensory scientist at Oregon State University who studies the chemical compounds behind flavors and aromas in wine.

It seemed like every winemaker in the state was trying to reach her. They needed to know right away what to do with their grapes. If they made wine, would it taste bad? Could she use her expertise and equipment to test their grapes before it was too late? The closest wine lab was in California and backed up for months.

She dropped everything she was doing to help — even though the air quality in Corvallis was so hazardous that campus had closed. A layer of soot covered everything in her lab. And FedEx wasn’t even delivering. That was on top of the other challenges of working in a lab during the COVID-19 pandemic, including a shortage of pipettes she needed to run the tests.

It took the OSU team a week to clean the equipment, replace air filters and get a special shipment of chemicals for the analysis. Soon, they were running dozens of samples a day.

“It was an interesting challenge, and I’m happy to say OSU rose to the challenge,” she said.

Extreme heat, drought and wildfires over the past few summers have tested every part of Oregon’s food industry. And OSU researchers like Tomasino are stepping up to help.

They are studying why Dungeness crabs are struggling off the Oregon coast, developing climate-smart potatoes, using virtual cattle fencing to create firebreaks in Eastern Oregon, and even finding ways to make beer more climate resistant.

In her first year as dean of the College of Agricultural Sciences, Staci Simonich has traveled across the state talking with farmers, ranchers and others in the food industry. They no longer question if the climate is changing. Instead, they want more strategies to respond.

“To the farthest regions of our state, everyone wants to figure out how to navigate the new climate changes we’re experiencing,” she said. “Everyone is bound together to figure out a path forward.”

It’s a complex challenge that involves people across many fields — not just agriculture and marine sciences, but engineering and economics as well. They are helping the state both respond to climate change and mitigate it, Simonich says.

Doing more with less water

One thing all Oregon farmers have in common is that they are worried about water — now and in the future.

Droughts have become more severe, frequent and widespread in Oregon over the past 20 years, according to the Oregon Climate Change Research Institute.

In Southern Oregon, a bellwether for the rest of the state, there’s often not enough water to go around, said Alexander Levin, director of the Southern Oregon Research and Extension Center in Central Point.

As summers get hotter and drier, water deliveries are starting later and ending earlier. Farmers are looking for more ways to conserve what little water they have.

Levin and other OSU scientists are helping make crops more drought resistant. On a six-acre test vineyard at the extension center, Levin is studying how much water wine grapes really need and the best way to manage it.

He tests different types of grapevines and experiments with the timing and amount of irrigation. Then he shares the results with growers.

So far, he has found that winegrowers in Southern Oregon can use 44% less water than federal estimates (11.4 inches a year instead of 20.2 inches) without harming the plants.

He’s also working with engineering students to design low-cost, open-source sensors that measure water stress in grapevines. They are in the early stages of testing 32 devices in vineyards. Eventually, they hope the sensors will control irrigation valves, so the vines are watered automatically only when needed.

Choosing heartier plants can also help crops survive with less water. But in the case of hops — essential ingredients in the brewing of beer — the most aromatic plants are often the most delicate.

Brewers are looking for new hop varieties that create “fun, hoppy beers” and are climate tolerant and disease resistant, said Tom Shellhammer, a fermentation science professor.

Popular hop flavors and aromas are often tropical and fruity, like pineapple, grapefruit, guava and papaya. The flavors come from potent compounds, called thiols, found in the hops. Many of the thiols in hops are flavorless until released in the brewing process.

But Shellhammer and his research partners have found a new way to bring out the tropical flavor in hops: genetically modified yeast.

“GMO yeast is an opportunity to unlock hop aroma in varieties that usually smell ho-hum,” he said. “It can turn a plain-Jane hop into a real winner.”

It also opens the door to new hop varieties that can survive extreme weather, all while brewing a more flavorful beer.

Growing ‘climate-smart’ potatoes

Some farmers are looking not only for ways to adapt and protect crops from new climate extremes, but also for growing methods that put less pressure on the environment. A $50 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture aims to make that possible with an important Pacific Northwest harvest — the potato.

Jeffrey Steiner, Ph.D. ’82, leads the five- year project for OSU, in collaboration with the University of Idaho, Washington State University, Native American nations, the Soil Health Institute in North Carolina, local tribe- and woman-owned businesses, and the potato industry.

Together, they are helping potato farmers and tribes become more sustainable and profitable through the creation and marketing of new “climate-smart” potatoes.

It starts with the soil. Project leaders are working with farmers to assess and improve their soil’s health by identifying additional growing practices — like using rotation crops in the off years between potato harvests — that will increase organic matter in their fields. The goal is healthy soil that retains more water and nutrients and releases fewer greenhouse gases into the air.

Steiner, the director of OSU’s Global Hemp Innovation Center, and his team applied for a USDA Climate-Smart Commodities grant on short notice, after first looking into it for hemp growers.

Potatoes were a better fit, because they are grown on such a large scale in the Pacific Northwest. More than 62% of U.S. potatoes come from nearly 500,000 acres in Oregon, Washington and Idaho. (Hemp is a potential rotation crop in the non-potato years, along with corn, alfalfa and cereal grains like barley.)

“We built this project from the ground up,” Steiner said. “We aren’t coming in with a package of recommendations. Instead, we’re talking with industry folks and Native American tribes to see what options work best for them and fit their production goals.”

Most of the grant money will go to farmers and tribes as incentives to help cover the costs and risks of changing their farming practices. In some cases, they may be learning new methods and how to use them to produce high-quality potatoes.

Steiner hopes the changes will pay off later when potatoes are marketed with premium “climate-smart” labels, like those used currently for organic produce.

“We hope the time will come when you can go to your grocer and choose potato products that were grown in a climate-smart fashion,” he said.

Harvesting the unpredictable sea

For 35 years, Jack Barth has been going out to sea off the Oregon coast to understand what’s happening under the surface. He’s an oceanography professor and the executive director of OSU’s Marine Studies Initiative.

“One of the most beautiful sights is to look back to the land and see the fog banks, coastal forest and the connection with the ocean,” he said. “It’s an incredible spot that we want to keep vibrant.”

Oregon’s fisheries are an important part of that land-sea connection and an economic pillar for coastal communities. Their most valuable species is Dungeness crab. But lately the crab season has been unpredictable and sometimes called off.

Associate Professor Francis Chan, center, talks at Otter Creek Marine Reserve. An ocean sensor is visible on the rocks. He and Professor Jack Barth have been studying the problem of ocean hypoxia since 2002. (Photo by Oregon State University.)

Barth and his research partner, Francis Chan, have been studying the problem since 2002, when crabbers pulled up their pots one day and every crab was dead. The problem: low-oxygen (hypoxic) zones made worse by warming waters and climate change. Other fish can swim away when oxygen levels are low, but crabs can’t get away fast enough. Young crabs are the most vulnerable because they are still trying to grow and build their shells.

Barth and Chan use remote sensors and underwater robots to measure conditions at the bottom of the ocean.

“We keep our fingers on the pulse of the ocean,” Barth said. “We have to know what’s going on out there.”

They have a new $4.2 million grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to study how stressors — like low oxygen, acidification, algal blooms, heat waves and rising temperatures — threaten marine ecosystems.

“We’re trying to put the whole picture together,” Barth said. “It’s when those things happen together that they are the most harmful.”

They are collaborating with research partners and Native American tribes to make maps of the risky conditions and see how they react together. Tribal members are collecting new data and sharing their knowledge of ocean patterns from oral histories going back hundreds of years.

Barth hopes to help the coastal communities he sees from research boats “stay successful and have sustainable harvests.”

Fighting wildfire with ... cattle?

On the opposite side of the state, cattle could soon have a role in fighting wildfires. And all they have to do is eat.

Ranchers can use new virtual cattle fences to create fire breaks on rangelands, a study by OSU and USDA researchers found. The cattle help stop the spread of wildfires by grazing on the nonnative grasses that fuel them.

Beef cattle are a nearly $600 million industry in Oregon and one of the state’s top food products. With virtual fencing, cattle could help protect the state’s other livestock and agricultural crops. It’s all done remotely with GPS satellites and receivers on their collars. When the animals stray outside the virtual fence, a sound or mild shock turns them back.

Oregon State University and the U.S. Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service fitted cattle with collars that apply a mild shock or play a sound when the animals step outside the borders of a virtual fence. Using this technology, cattle can be corralled into place to create firebreaks while they graze. (Photo by Morgan Lawrence.)

The idea for virtual fences has been around for a while, but technological advances, like longer-lasting batteries, have made them more practical, said David Bohnert, the director of OSU’s Eastern Oregon Agricultural Research Center in Burns.

Virtual fencing can be less expensive than physical fences or clearing land with machinery and labor, he said. It can be used to keep cattle away from riparian zones where salmon and steelhead spawn. Ranchers can also use it to track the cattle in real time from their cell phones.

“This is a potential game changer for land management,” Bohnert said. “It gives us another tool that is super flexible and pretty powerful.”

Getting ready for next time

The fires of 2020 were a wake-up call for the Oregon wine industry, Tomasino said. It showed winegrowers that they could no longer rely on out-of-state labs for smoke testing. They needed their own.

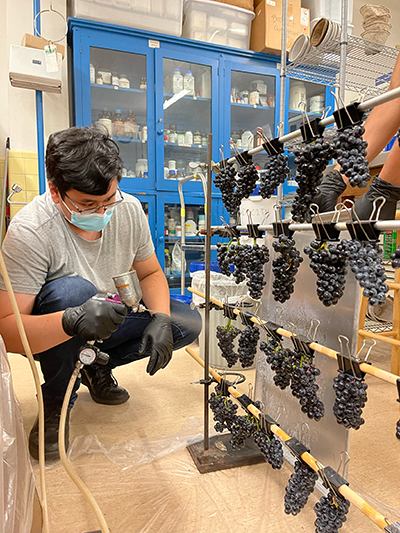

Master’s student Trung Tran, ’20, sprays protective coatings on grapes to test whether it’s possible to prevent smoke compounds from penetrating the fruit. Preliminary results show that two of the coverings appear to help. (Photo by Clara Lang.)

Industry leaders successfully lobbied the Oregon Legislature for $2.6 million to open a permanent OSU wine and smoke lab this spring.

“It feels really good to have somebody looking out for us,” Klingner, the winegrower, said.

Tomasino also won a $7.65 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to lead a four-year study of smoke taint in wine with UC Davis and Washington State University. It’s no wonder Wine Enthusiast magazine named her one of their “Innovators of the Year.”

Since 2020, Tomasino’s lab has identified key compounds that cause smoke taint. She is working to establish guidelines for winegrowers, so they know exactly how much smoke grapes can take. And she has placed smoke sensors in vineyards to track exposure. “We don’t want 2020 to happen again, but if it does, we’ll be prepared,” she said.

Last summer, Klingner looked across her vineyard with concern as smoke from wildfires once again rolled across the leafy rows. This time, Tomasino was able to check a newly installed smoke sensor and tell her not to worry.

But there’s still a lot to learn about how to protect crops from new climate extremes. “We need people who are dedicated to doing this,” Klingner said, “and OSU is the most appropriate place to do it.”