From the Winter 2023 issue of the Oregon Stater magazine

Tucked away in a corner of Cordley Hall in Corvallis, there was, for a short time, an amazing but tiny museum. Its artifacts ranged from medals to original artworks to photos, but there were no admission fees or interpretive plaques, and — alas — no gift shop. In fact, this unusual museum wasn’t open to the public at all and, at least for now, has been packed into boxes and stored away; whether it will ever exist again is unknown.

The museum’s subject, curator and docent was Jane Lubchenco, Wayne and Gladys Valley Chair of Marine Biology. As administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for President Barack Obama and current deputy director for Climate and Environment in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, she has amassed an astounding collection of mementos, medals, award citations and other artifacts that document her storied career as a marine ecologist and a leader in environmental conservation and policy. Before storing these treasures away in preparation for Cordley Hall’s remodel, Lubchenco spread them out in an empty office and allowed a few visitors to wander the collection and hear the story behind each piece. Here are some highlights.

Gift from a senator

While Lubchenco was no stranger to politics prior to being asked to join the Obama administration in 2008, some of Washington’s machinations proved challenging. Nominated along with the President’s Science Advisor for science-related positions in the administration, she was surprised that their Senate confirmations were put on hold.

“We were ready to go, the Senate was ready to vote for us,” she recalls, “but the Senate has these arcane rules where somebody can put a hold on you, and they don’t have to say why. They just say, ‘I’m not going to let this move forward.’” Lubchenco didn’t even know which senator had requested the hold.

A Washington Post investigation revealed the culprit to be Senator Robert Menendez, a Democrat from New Jersey, and his actions had nothing to do with either of the nominees — he was hoping to gain traction with the president on an unrelated issue.

“His constituents, especially the scientists at Princeton and Rutgers in New Jersey, bombarded his office saying, ‘How dare you hold up these really important science positions. These are fantastic candidates.’ All of a sudden, the hold was released, and we sailed through,” Lubchenco says.

The next day this U.S. flag arrived in her office, a gift from Menendez. It had been flown over the Capitol at his request in honor of her confirmation — an apology of sorts.

Lubchenco on ice?

Lubchenco on ice?

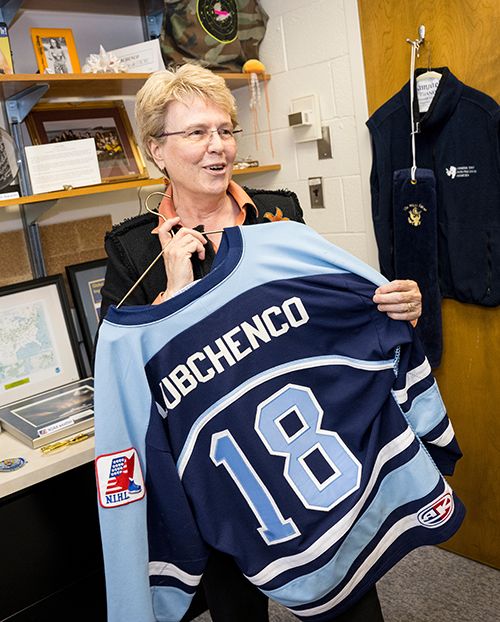

One of the mini-museum’s standout artifacts is a blue and white hockey jersey emblazoned with the scientist’s name across its back. With no skates in evidence, what was the story behind this? A competition was involved, Lubchenco explains, but one with robots rather than hockey sticks.

NOAA’s National Marine Sanctuaries program includes the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of Michigan — a spot rife with historically important shipwrecks. The creation of the sanctuary jump-started the local economy, drawing tourists to explore the wrecks and creating new business opportunities and jobs for the locals. NOAA also organized a series of robotics competitions for local high school kids to explore the shipwrecks using underwater robots of their own design. “Many of the students discovered new skills and passions, and envisioned careers they had never imagined,” she says. “The local youth hockey team was so excited when I visited that they decided to give me a team jersey.”

A gift from the sea

Lubchenco’s work on marine protected areas, in both the science and policy arenas, has made her an invaluable advisor to organizations and governments around the world looking to protect local marine resources. For example, she was invited to Easter Island to advise the Rapa Nui people and the Chilean government on establishing a marine protected area program there. A Rapa Nui chieftain gave her this necklace made of fish vertebrae and sea urchin spines to thank her for her time and advice. Lubchenco holds this piece in special reverence, as she explains, “You are not allowed to take anything off the island, except what is given to you, or a piece of art that is made for you.”

A sea star for a stellar leader

Lubchenco takes inspiration from one particular denizen of the deep: the humble sea star. “Sea stars don’t have a single brain — they have a network of ganglia, like an integrated, distributed network. So, the sea star, for me, represents leadership that is inclusive and empowering, where you’re sensing information from multiple places to inform an integrated decision. And that’s the way I run my teams,” Lubchenco says. Given this philosophy, it’s entirely fitting that she is proud of a glass sculpture featuring a sea star and the cosmos created by noted glass artist Eric Hilton to honor her work.

Of portraits and fish prints

Portraits abound in the mini-museum: photos of Lubchenco with dignitaries and celebrities, cartoons drawn featuring her, even a poster of Wonder Woman with Lubchenco’s face. But none is more intriguing than the portrait created by gyotaku artist Dwight Hwang, another copy of which graces the walls of the new Gladys Valley Marine Studies Building at the Hatfield Marine Science Center in Newport.

Gyotaku is the art of fish printing — applying paint to an actual fish or other creature and then transferring the fish’s image onto paper. Paint was indeed applied to Lubchenco’s face, then the rest of the portrait was made by inking and pressing various marine species onto the paper, mosaic-style. Her hair is made of octopus tentacles, her collar created with sea stars, crabs, kelp and more. The artwork captures what she loves, what she has studied as a scientist and what her career has been dedicated to protecting.

Oxford honor

Lubchenco is the recipient of 24 honorary doctoral degrees from institutions across the nation and the world. Her most recent, from Oxford University, was announced in 2020 but wasn’t awarded until spring 2022 due to COVID delays. The Oxford degree is accompanied by a short, poetic summary in English and in Latin. It was read by the chancellor at a ceremony called the Encaenia. It concludes, “She believes in using science and engaging society to solve our biggest challenges” — an apt summary of her life’s work.

Still, for all the honors and kudos Lubchenco has received, she saves her highest praise for her home university. “I can’t imagine doing anything more fun and rewarding than working with our amazing students and with world-class colleagues to have a local and global impact,” she says. “I think that’s part of the Oregon State mentality, the philosophy of enabling science to thrive and to deliver for people and communities by connecting science to policy.”